ChessWalk

What if you could find the exact moments where stronger players outthink you, and steal those moves?

Introduction

Every chess player learns from stronger opponents. But what if you knew exactly where stronger players choose a different move—and that move wins more games for people at your rating?

That's the core idea behind ChessWalk, a tool I've been co-developing with my friend Jason. Engine analysis tells you the "best" move, but not necessarily the move that wins more games at your level. This tool uses Lichess data to find positions where stronger players make different choices—and those choices actually improve win rates for lower-rated players.

Let's take a closer look.

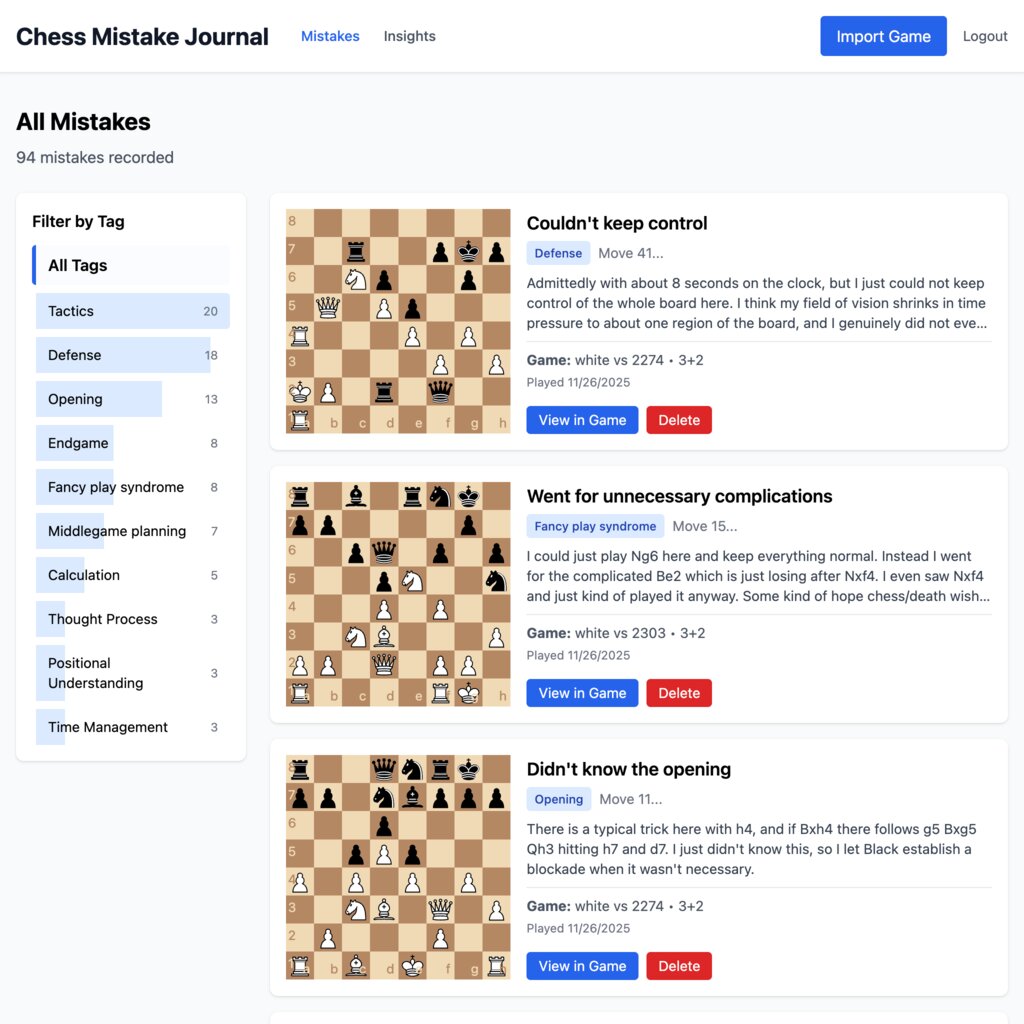

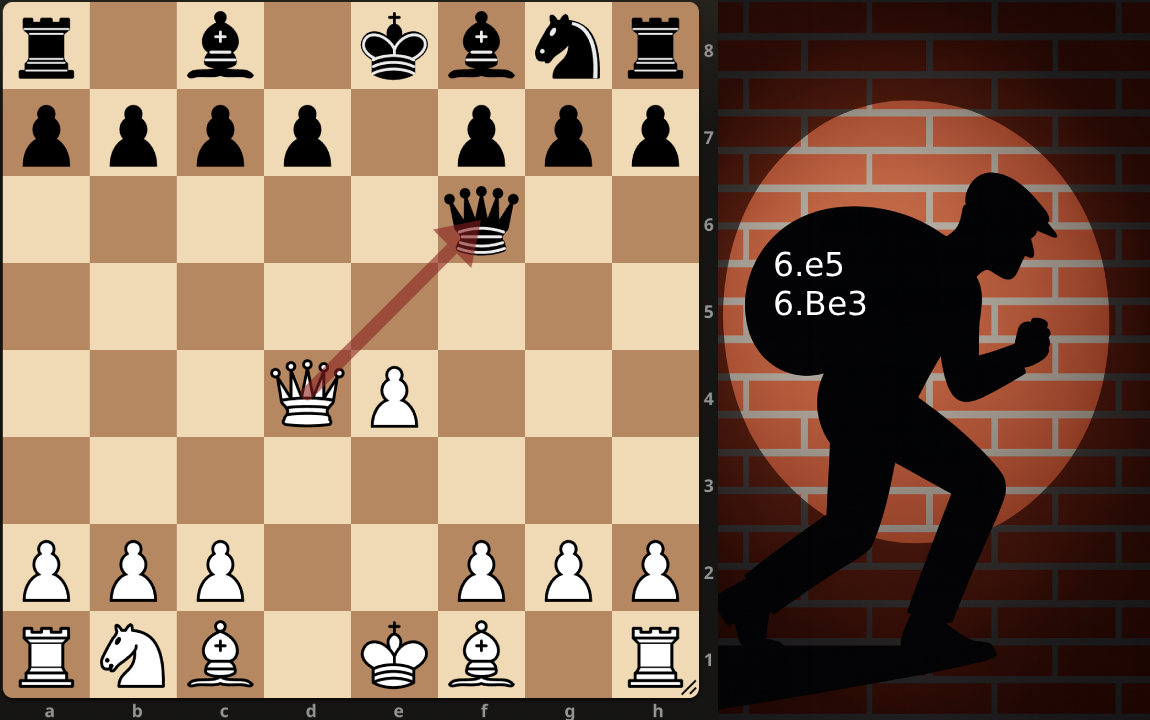

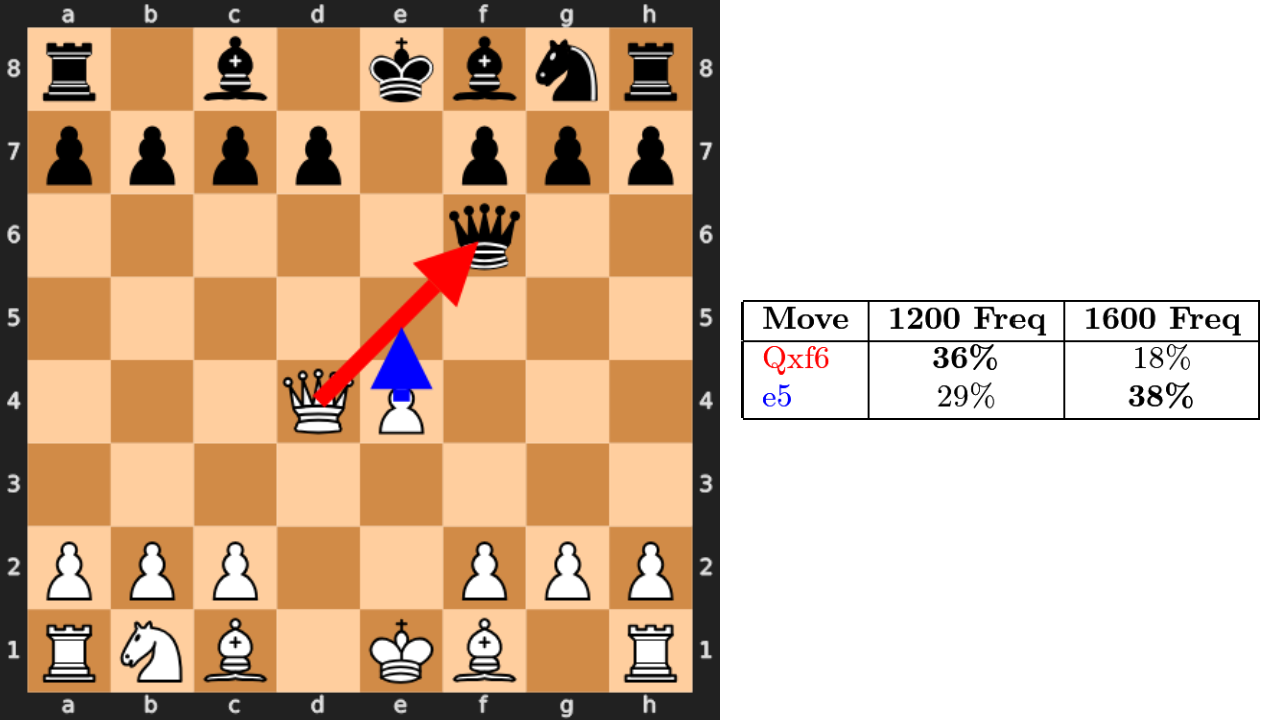

Example 1: 1200s vs 1600s

Comparing what 1200s and 1600s do in the same position.

Takeaways:

- 1600s choose e5 over Qxf6 by a factor of more than 2×.

- 1200s have the reverse preference, choosing Qxf6 over e5 by a factor of ~1.25×.

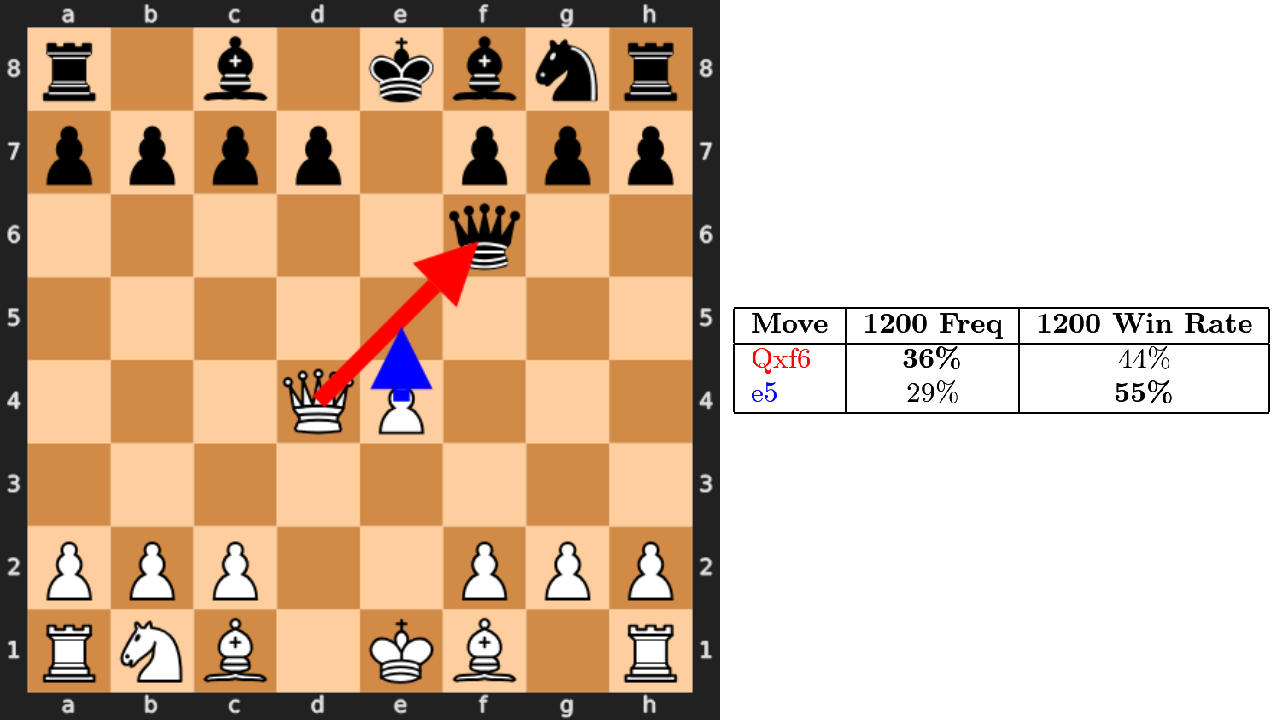

Okay, so maybe 1200s should be playing e5 more. But to be sure, we should check the win rate data of the two moves.

Win rates for 1200s choosing e5 vs Qxf6.

Bingo! When 1200s do play e5 instead of Qxf6, they have a +11% win rate! So if you're in the 1200s yourself, studying moments like this one can help you think more like the next tier up.

Why the difference?

- 1200s see a Queen trade and figure it's even, without considering the aftereffects.

- 1600s recognize Qxf6 Nxf6 as replacing White's Queen with a Black Knight—worsening board control and tempo—so they reject Qxf6 in favor of active moves like e5.

We didn't just stumble upon this position by chance, though. Here's how the process works.

How we find these moments

- Pick two rating cohorts (say, 1200s and 1600s).

- Take a random walk through the Lichess opening tree, following moves that the lower-rated cohort actually plays, one ply at a time.

- At each position, compare the move frequency in both cohorts.

- Use a Chi-squared test to check if the preference difference is statistically significant.

- If yes, see if the higher-rated choice improves win rate for the lower cohort.

- If yes, add it to the example bank.

Let's see what happens further up the rating ladder with 1400s vs 1800s.

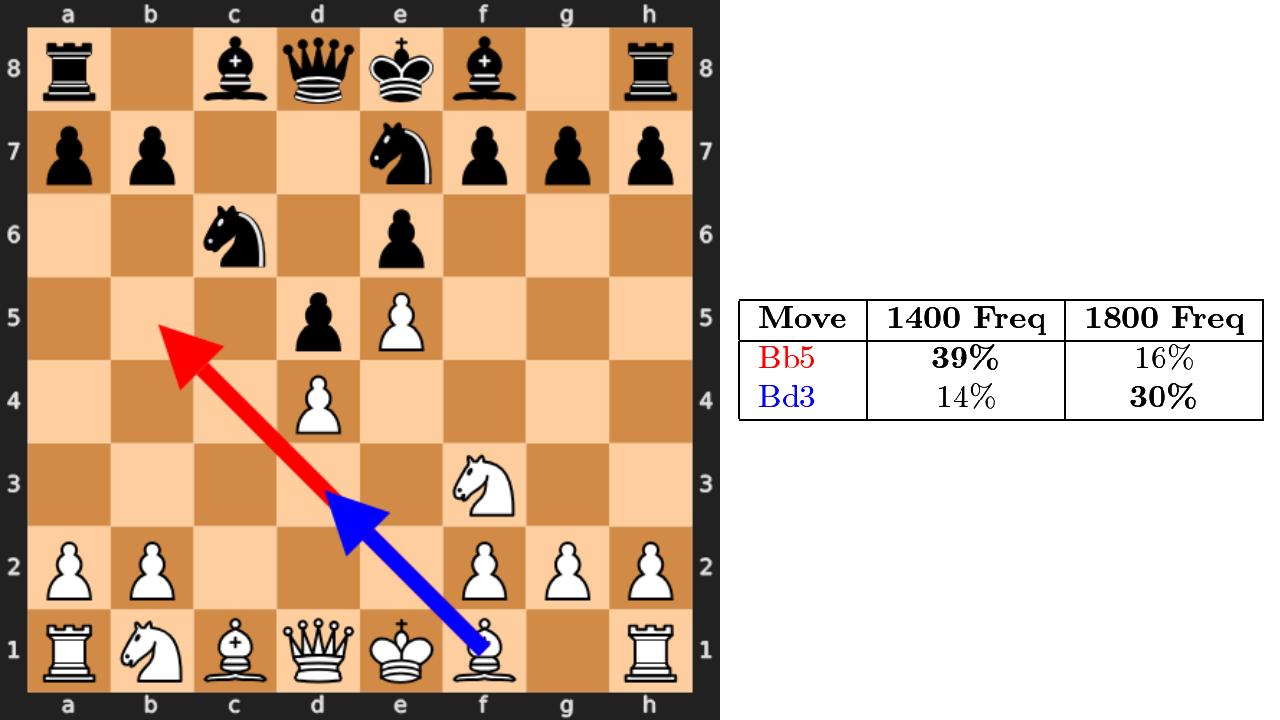

Example 2: 1400s vs 1800s

Comparing what 1400s and 1800s do in the same position.

Takeaways:

- 1800s are almost twice as likely to choose Bd3 over Bb5.

- 1400s reverse that, choosing Bb5 over Bd3 nearly 3× more.

However, when I looked at the win rate data, switching to Bd3 raises 1400 win rates by +7% (52% vs 45%).

Why the difference?

- 1400s feel the Knight pin is aggressive, but here it's easily neutralized with Bd7.

- 1800s see more long-term value in the b1–h7 diagonal.

(Side note: the engine slightly prefers Bb5 to Bd3, but the goal here is to find what actually wins more games at your level.)

Let's look at one final example even higher up, comparing 1600s to 2000s.

Example 3: 1600s vs 2000s

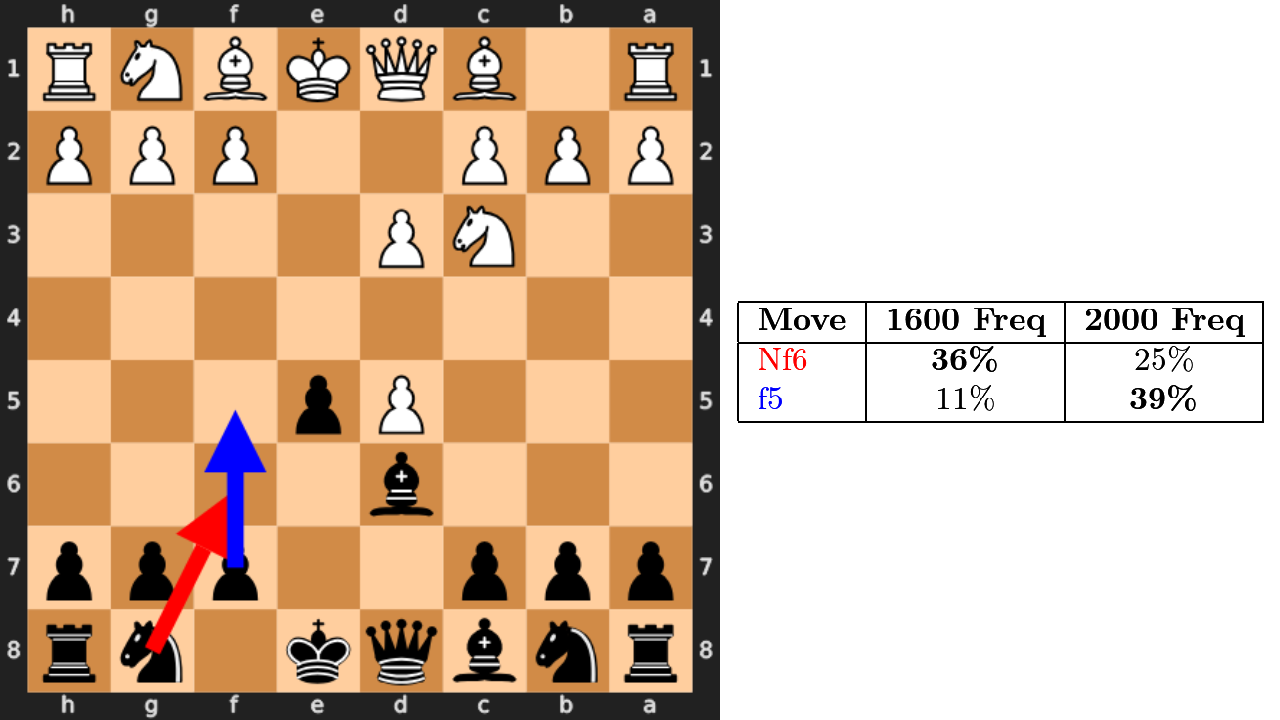

Comparing what 1600s and 2000s do in the same position.

Takeaways:

- 2000s are ~1.5× as likely to choose f5 over Nf6.

- 1600s have completely inverted preferences, going for Nf6 more than 3× as often as f5.

However, when I looked at the win rate data, switching to f5 boosts 1600 win rates by +8% (55% vs 47%).

Why the difference?

- 1600s default to "develop the Knight."

- 2000s know that setting up the e5/f5 pawn duo is effective here since White can't exploit the usual weaknesses it leaves behind.

Why not just ask the engine?

Sure, you can drop any position into an engine and get a 3600+ move suggestion. But copying engine moves has issues:

It's inefficient. You don't necessarily know which positions are the key ones to check. It can show you big blunders, but it might miss other crucial moments.

It's optimized for superhuman play. A +0.3 engine move might be theoretically better than a +0.1 engine move, but it might lead to hard-to-handle positions for human players. The ChessWalk method specifically discovers moves that work in practice at the human level.

Where to go from here

The examples above are just a taste. You can check out the growing ChessWalk collection at chesswalk.streamlit.app and start training yourself to spot these rating gap moments.

For coaches, certain patterns may emerge from typical mistakes at the different levels. In the future, we may also consider starting the random walk from a specific opening setup so that the positions we add to the bank are tailored to certain openings.

Interested in lessons, workshops, or custom tools?

Get in touch →